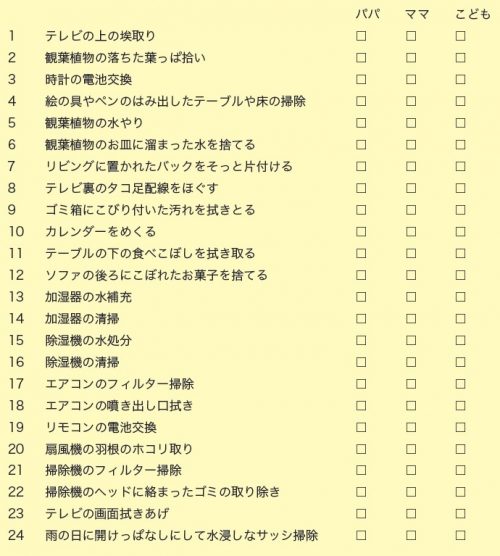

Even if they are not named, each one is important, and the number of them is enormous!

The “nameless chores” are daily chores that are difficult to categorize under the broad categories of cooking, cleaning, laundry, etc. I have compiled a list of 148 such chores. I have compiled a list of 148 such chores and categorized them by location, for example, “dust the top of the TV” or “pick up fallen leaves from houseplants” in the living room, “refill the ice machine” or “open and dry milk cartons” in the kitchen, “remove scales from the washroom mirror” in the bathroom, and so on. I have listed a variety of detailed items, but I am sure there are many more for some people.

I want you to notice! Household chores that “someone” is doing before you know it.

One of the most common things we hear about “the chore with no name” is people wanting to realize that there is work to be done there. In many cases, “whoever notices, does it when they notice” in the family, and the burden inevitably falls unevenly on someone else. Even if each task is a small one, the sheer number of them tends to accumulate frustration. It would be nice if we could casually say, “Please take care of this,” but the details are so small that it is difficult to ask someone to take care of every single thing.

In addition, we often hear from mothers that they are glad that their fathers share household chores with them, but they are concerned about the half-heartedness of the work. For example, “He changes diapers, but leaves the changed diapers in the living room,” or “He washes dishes, but leaves the dishes in the draining basket. Someone has to take care of the diapers left in the living room, and someone has to put the dishes back in the cupboard after noticing that they have been left there. The “chores with no name” often stem from things being done halfway like this.

Household chores are not “something to be finished” but “preparation for the next use.

To solve the problem of “chores with no names,” it is not very effective to set rules for each and every one of them. If you set too many detailed rules, such as “Throw away the dishes when you are done using them” or “Put them away after washing them,” your household will become cramped. Therefore, one of the points I often tell people is the idea that chores should be “prepared for easy use by the next user.

For example, cooking and washing up is not the end of the process. After that, there is still the work of preparing the rice. I think of housework as a set of tasks that include sanitizing cutting boards and sponges, sharpening kitchen knives, cleaning the inside of the microwave oven, and other preparations that make it easier to use the next time you cook.

When doing household chores, try to do them with the next person in mind. Your family’s reaction will probably change from “You’ve done all this, why can’t you do this?

This change in mindset is also useful when communicating to children. If a toy is left uncluttered and you are halfway through the process, you can easily teach them the true meaning of cleaning up by saying, “If there are toys left lying around that are lost, you will have a problem the next time you play with them.

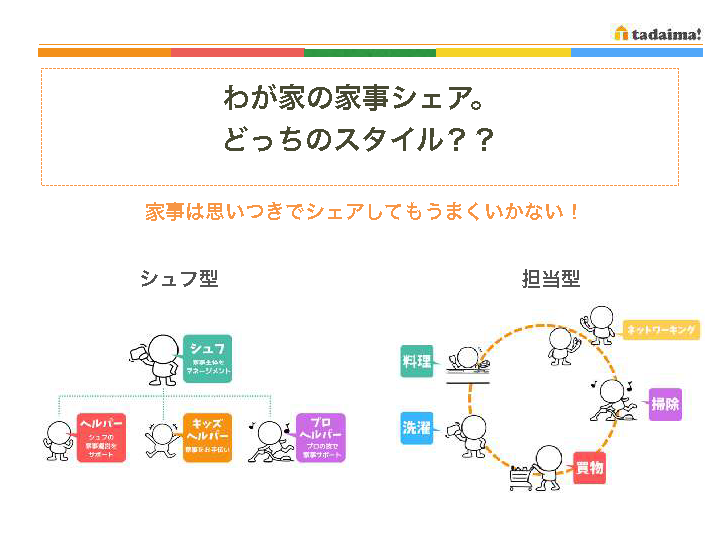

What are “shufu” and “in-charge” styles of housework sharing?

While each family has its own style of housework sharing, after talking to thousands of people over the past 10 years, we have realized that there are two main types: the “shufu (househusband/housewife) type” and the “in-charge type.

In the “shufu type,” a shufu manages the entire housework, and helpers support the shufu and share the chores under the direction of the shufu.

The shuffler role is suited to people who want to do household chores their own way, while the helper role is suited to people who would appreciate detailed instructions.

In addition, families with a clear division of roles, such as “you work, I do the housework,” or in dual-earner families where there is a large disparity in housework skills, are more likely to be “shufu-type” families.

In the “in-charge” style, household chores are shared by clearly defining responsibilities, such as “Dad does the cooking, Mom does the laundry, and so on. This style is suitable for people who are able to leave the cooking and laundry to the other person’s way of doing things without detailed instructions, or for people who are more comfortable with being left to do things completely rather than being given detailed instructions.

I am often asked, “If we are going to share housework, is it better to be in charge than to be a “shufu” type?” However, the best style depends on the situation at the time, such as the couple’s life-work balance, etc., so I think it is best to start with whichever type is easiest for them to do.

Let’s decide “when to do it” and “by when.”

In “shufu-type” households, the most stress is concentrated when giving and receiving instructions. Both parties are easily frustrated.

Therefore, in the case of the “shufu type,” the key is to decide “when to do it. For example, simply saying, “I’ll clean up after dinner,” is enough to make both parties feel comfortable sharing household chores.

The most important point in the “take charge” model is the autonomy of the person in charge, so the one word that takes away that autonomy-“When are you going to do it? is not allowed. However, it is important to decide “when to do it by” because if you don’t tell them, they may not do it forever. If you set a deadline, you can say, “It’s not done yet,” when they don’t do it after that. The person in charge may be annoyed at the moment they are told, but since it is you who is breaking the promise, it is not unreasonable, and you can share the chores amicably with each other.

Parallel Housework” to Reduce Burden and Eliminate Frustration

The two main causes of frustration related to housework are “burden” and “dissatisfaction. The burden is the time and effort involved, and the frustration is the unfair feeling of “I’m all alone. Parallel housework” is an effective solution to this problem.

The rule is to do household chores at the same time, with the person who is “not ____ doing ____ doing ____.” If the person who is not cooking prepares the bath, the person who is not cleaning does the laundry, and so on, the sense of cooperation is eliminated, and the burden is reduced.

If you think that neither the “shufu type” nor the “in-charge type” might be suitable for your family, we recommend that you try the “parallel chores” approach.

Build family trust by sharing chores!

We often hear laments from mothers who attend our housework-sharing lectures that their fathers show no interest when they talk about housework-sharing. It is more important to change one’s own awareness than to try to change the other person’s. Just by changing the way you send out information, such as setting a deadline and asking for help, something will gradually change.

Consideration for others is essential for a family to be comfortable with household chores. Sharing helps to improve mutual trust. If we are aware that housework can be a process of building family relationships and trust, even if it is a “chore with no name,” it is less likely to cause dissatisfaction and differences within the family.

Tomoyu Miki / Housework Sharing Researcher

After working for a remodeling company, he went freelance in 2006. In the course of her work, her interest expanded from a comfortable “home” to a comfortable “family”, and in 2011 she started a non-profit organization, tadaima! I want more and more families to be able to say “I’m home! I want to increase the number of homes where people want to come home and say “I’m home! He has appeared on TV programs such as NHK’s “Asa Ichi” and TV Asahi’s “Tokyo Sight”, and in magazines such as “Orange Page”, “Tamago Club”, and “Nikkei Trendy”. He is the author of “Katei de moeme nai kuritsu zukuri” (“Creating a room that doesn’t suffer from housework”) published by Hinokashi Shoten. He is also the author of the e-mail magazine “tadaima Tsushin! a mail magazine, offers tips on how to build a “home you want to come home to.